THE FUTURE OF CORPORATE REPORTING

ABSTRACT

The key to long-term success is the quality of leadership and its influence on all a company’s relationships. Communication - alongside strength of character and strategy - is in turn at the heart of good leadership and relationships. Reporting is in its turn one aspect of strong communication, and a particularly important art in creating a sense of confidence in a company. Over the last decade Tomorrow’s Company has played a significant role in charting the course taken by leaders in their companies’ communication to their many stakeholders, and also in clarifying what these different stakeholders need and can expect. In ‘Restoring Trust’ (2004) we described the value chain that links the ultimate investor to the company, and suggested how transparency and rewards could be better aligned along that chain. ‘Sooner, Sharper, Simpler – A lean vision of an inclusive Annual Report’ (1998 and republished 2006) formed the basis for the mandatory Operating and Financial Review (OFR) and outlined a number of principles we believe should be followed by companies, regulators, investors and stakeholders in the UK. Regulations are becoming more global – with all the complications that brings – and there has been a growing worry about class actions against companies based on what they say about the future. But, in our view this does not change the principle of good communication. This publication reviews where UK-based companies now think that they are and suggests what they should be preparing for as the fog clears after the regulatory confusion of 2006.

KEY WORDS: Corporate, Financial statements, financial strategies, corporate social responsibility, reporting

INTRODUCTION ::

When Gordon Brown overturned the planned introduction of the UK’s OFR in November 2005 it was because of the “extra administrative cost” that a “gold-plated regulatory requirement” would impose on businesses.[1] But investors, accountancy bodies, trades unions and environmental groups immediately attacked the decision, saying it would “damage information to shareholders”.[2]

Whatever the rights and wrongs of that decision, the next six months saw the Accounting Standards Board (ASB) publish almost all of the planned OFR as its “statement of best practice” for narrative reporting.[3] And for annual reports published after 1 January 2006, the 2003 Accounts Modernization Directive from the European Union (EU) came into force – legislation with a much wider impact than the OFR, requiring more than 37,000 unquoted as well as quoted companies in the United Kingdom to disclose much of what the OFR would have required, in a new-style ‘enhanced Business Review’.[4]

Just over a year on from the Chancellor’s decision, where do we find ourselves? Have companies avoided OFR-type narrative reporting because of the cost? Have they rushed to embrace it as best practice, even though there is no legal requirement to do so? Or are they caught between differing UK and EU requirements, unsure what to do?

This short report looks at how companies have changed their reporting style, both before and after the introduction of the enhanced Business Review. It examines the reasons behind their actions, and makes predictions for how we should expect this area to evolve in the upcoming reporting season following the year ends in December 2006.

PROBLEM WITH REPORTING ::

The roots of the OFR lie more than 10 years in the past, when there was a drive to change Company Law to achieve three major things: to clarify directors’ duties, to encourage shareholders to exercise more control, and to improve transparency and accountability. With the reporting failures at Enron and WorldCom in 2002, the government decided to move faster on the third of these priorities, and so the OFR was born.

The intention of the OFR was to “improve transparency of corporate governance and hence business performance.” In doing so it would “focus both directors' and shareholders' assessment on all internal and external issues affecting that performance.”[3] No wonder, then, that a number of groups described its repeal as leaving a significant “policy vacuum.”

But the 2003 EU Accounts Modernisation Directive also requires companies to prepare an enhanced review of their business. It requires them to report on risks and uncertainties to a level not previously experienced in the UK.[4] Although it does not go as far as the OFR in requiring companies to report on strategy and the prospects for the business,[4] the January 2006 decision by the ASB to issue the planned legal ‘Reporting Standard’ as a ‘Reporting Statement’[5] provided a clearly-defined ‘statement of best practice on OFR’ for any company that wishes to follow it – irrespective of whether or not there is a legal requirement to do so.

The fear in some quarters was that narrative reporting would not be as good as it would have been with compulsory OFRs.[6] But rather than a reduction in quality across the board, it seems more likely that this will create a divergence in what companies do. Some companies may only conform to the minimum; others will continue to push back the frontiers.

The key question in determining whether or not this causes a problem, and whether or not it is useful to publish an OFR, is ‘what does the company want to achieve by publishing its annual report?

WHY ANNUAL REPORTS? ::

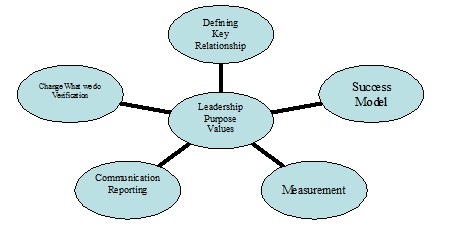

For Tomorrow’s Company, the annual report is part of the whole virtuous circle of governance for a business (see Figure 1). Whatever the legislative environment, there is something deeply natural about the directors giving an account of their stewardship. We all need to be accountable to be effective, and the annual report and the Annual General Meeting (AGM) are the axles which drive this accountability.

But the focal point which determines the quality of the annual reports produced is the perceived self-interest of the companies that create them. What do they see as the purpose of creating an annual report?

Figure 1:

GOVERNANCE – A VIRTUOUS CIRCLE ::

The virtuous circle of governance is a joined-up way of thinking about success. It means linking together every conversation about business planning, measurement, and the boardroom agenda, with the production/audit of the annual report (and other reports), the annual meeting, and stakeholder dialogue – all as part of the same logic.

Reporting on performance provides verification of whether or not the company has achieved what it set out to do. This in turn allows it to understand whether or not it has correctly identified its key relationships and success model, and to change these as necessary. This allows it to define how to measure its success model, so that it can be communicated. There is also another set of impacts that flow is the opposite direction. Communicating (for example through an annual report) forces the company to define what measures it is going to report on. This in turn forces it to be clear about what is its success model, and what are the key relationships that enable that model to succeed. This also forces the company to be clear about what it means by success: what it is setting out to achieve.

This is why companies find non-financial reporting difficult – because it forces them to be explicit about the success they seek and what drives it. It also explains why those that choose to grasp the nettle gain so much benefit from doing so.

A recent study[7] by the design agency Bostock & Pollitt found that companies have two main reasons for producing an annual report. The first is to meet the government’s regulatory requirements. The second is to market the company to key stakeholders. Who are these groups of stakeholders? The same survey gives us some insights into the breadth and variety of different audiences that companies feel they need to communicate with (in priority order):

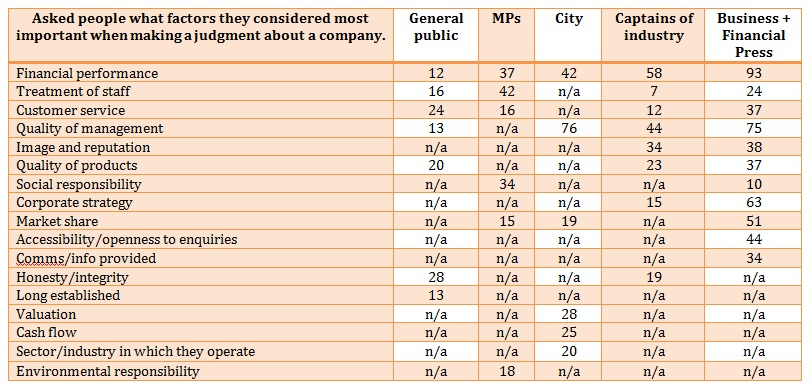

WHAT DO THE DIFFERENT STAKEHOLDER GROUPS WANT FROM THE ANNUAL REPORT?

These varied and diverse groups are likely to be interested in very different aspects of the company. Each group will want to see its own interests reflected in the annual report.

“What are the most important factors you take into account when making a judgment about a company?” (Spontaneous, top two factors for each group highlighted)[8]

For companies, as we saw, the primary stakeholder group is overwhelmingly the existing shareholders and potential investors. What do these people want from an annual report?

What is the solution? Can the circle of differing needs be squared within a single annual report?

WHAT IS THE SOLUTION?

Companies want to meet their legal requirements. They also want to communicate with their key stakeholders. The law provides a framework within which companies are free to find their own solutions. The ability to report online will make this task easier.

From early 2007, the proposal is that UK companies will be legally allowed to use the internet and email as the default option for sending information to shareholders, sending paper copies of annual reports and other information only to shareholders who request them9. The DTI estimates that this will save UK-listed companies over £47 million a year. But the main benefit of online communication, surely, is not that it reduces cost but that it allows companies to develop detailed, targeted communications and relationships with each of the major stakeholder groups that can impact the business performance. It is business-criticality and materiality that is key.

For investors and investment analysts, the annual report is already somewhat of a non-event[10], since by the time it is published they have often already received far more in-depth information from other sources throughout the year. For them the annual report is already “a supplement to give context.”[7]

Wider use of the internet should allow companies to develop similar strong relationships and communications with their other major stakeholder groups. This should improve the quality of their relationship with each constituency, and hence lead to improved business performance.

All this is positive. But it raises the question: what role remains for the annual report? If new technologies allow better communication with key stakeholders by other means, has the annual report had its day? Is its only remaining role to meet the company’s legislative requirements?

At Tomorrow’s Company we believe that the annual report has a far more positive role to play in the whole process of governance and accountability. If companies are to fulfill both their legal and wider communications responsibilities effectively, they need to be very clear about their objectives. They also need to understand where the annual report fits as part of their total communications approach.

But before we look in detail at what we believe that role is, let us first examine the changes that companies have actually made to their annual reports over the last 12 months. These are the annual reports for the year-ending December 2005 (when companies would have been readying themselves to comply with the OFR) and for the year-ending April 2006, when the enhanced Business Review was required for the first time.

HOW COMPANIES HAVE CHANGED THEIR REPORTING?

When the corporate reporting agency Black Sun analyzed the FTSE-100 annual reports published for the year ending December 2005[11], they found evidence of significant change:

- 95% of companies discussed their corporate strategies, up from 75% a year before

- 40% provided business objectives or targets, up from 16%

- the percentage of firms discussing values and principles rose from 30% to 66%

- the proportion disclosing Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) almost doubled from 19% to 36%.

But was this actually because companies had been expecting to have to comply with the OFR? Now the legislation had been repealed, would standards slip?

In August 2006 Black Sun published a follow-up report[12] that looked at the annual reports published by the FTSE-100 companies with April year-ends. Although the expected OFR had not come into force, these companies were the first to have to comply with the new EU legislation and publish an enhanced Business Review. Although this legislation was seen as less demanding than the OFR, some firms were found to be “struggling to meet the more challenging aspects”, while others “demonstrated how to use the opportunity to communicate – with conviction and commitment – meaningful information about what is driving their performance.”

Interestingly, despite the fact that the mandatory OFR had been repealed, nearly half the companies (48%) still felt it meaningful to describe their narrative as an ‘OFR’. Of those companies, half (26%) explicitly said that they had prepared their reports in accordance with the voluntary principles of the OFR Reporting Statement issued by the ASB.

At a high level, then, a significant proportion of Britain’s largest companies are stating that they find value in the OFR.

Looking in more detail at the basic building blocks of the Business Review:

- risk and uncertainties

- forward-looking information

- financial and non-financial KPIs

In September 2006, creative consultants Radley Yeldar published similar findings in a review of the most recent annual reports for all FTSE 100 companies, covering year-ends in December 2005 and April 2006[13].

They, too, found evidence of major changes in company reporting, with some areas still proving challenging:

- 83% included “some form of upfront strategic content or discussion”

- 43% called their narrative content an OFR, despite the switch to the Business Review legislation

- 37% made a “reasonable attempt at explaining their marketplace”

- KPIs were “getting better”, with 14% “fully defining or explaining their KPIs”

THE FUTURE ROLE OF THE ANNUAL REPORT ::

Companies want their annual reports to achieve two goals: to fulfil their legislative requirements and to communicate with stakeholders. Adequate communication with stakeholders can no longer be achieved by publishing a single report each year. Investors are already used to receiving information in a variety of different forms throughout the year. Through the use of the Internet companies are now building similar ongoing relationships with other groups of stakeholders. Investors receive quarterly announcements, ad hoc briefings, and the detailed reports required by different stock exchanges. The audiences interested in Corporate Responsibility (CR) or Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), for example, are finding that a number of companies now publish separate CSR reports, as well as putting information online:

“A couple of pages [on CSR] are included in the annual report, broad coverage online.”

“[CSR reporting] will become more complex as the environmental impact becomes more complex. Also online for CSR should be huge since one can do so much more… [It] will eventually be as voluminous and frequent as financial reporting.”

“This year was different in that we have moved away from a distinct CSR report or section because it has become so embedded in what we do.”[7]

These changes are moving all stakeholder communication away from being a one-off ‘event’ into more of an ongoing process or relationship, and we expect this trend to continue.

This points the way to a clearer role for the annual report.

At Tomorrow’s Company, we believe that successful companies achieve this by the ‘five plus one’ approach. In this the ‘five’ are the strong relationships (with customers, suppliers, staff, shareholders, and society) and the ‘one’ is leadership that aligns them to a common purpose. Companies, as we have seen, are already building relationships in depth with each of their five stakeholder groups. The role of the annual report is to enhance the sixth element: leadership.

The annual report cannot and should not focus on every single issue that is relevant to every single stakeholder. The annual report should focus on the issues that are material to the business as a whole, and bring them together in a single, coherent story. It should reveal the ‘value proposition’ of the total business.

Communications and accountability are the hallmarks of good leaders, and that is the role of the annual report: to summaries all the critical issues that affect the success of the business, explain how they have created the past year’s results, forecast how they might pan out in the future, and explain what is being done to ensure the company’s future success in that environment.

In doing so (see Figure 1 ‘Governance – A Virtuous Circle’) management’s understanding of the business is also enhanced, and so leadership is improved. This is reflected in the comment above about how CSR has shifted from a separate, reporting-focused activity to becoming “embedded in what we do”.

As we know, investors also want this viewpoint. They want an annual report that:

“…gives a good investment case, details of business drivers and strategy, puts this in the context of the marketplace and describes any risk factors that might face that company.”

“…[provides] a basis by which a reader can understand what is happening, the market the company is in…the company’s strategy to compete in that marketplace, how it is managing critical assets and resources in order to deliver on that strategy…”[7]

And this is exactly what the OFR and the enhanced Business Review set out to do.

Little wonder, then, that as understanding of the OFR and narrative reporting has grown, so opinion amongst the investment community has moved strongly in favour of these reporting frameworks.

A study published by IR Magazine in June 2006 showed that 78 per cent of fund managers and analysts believed companies should publish a full OFR. As a stand-alone figure, this is high. But it is even more striking when you realize that it is almost twice the number who had shared that view a mere eight months earlier. An Ipsos-Mori poll quoted to the Chancellor in October 2005 showed only 41 per cent of fund managers supporting the compulsory OFR[14].

As they gain experience and understanding of narrative reporting, companies and investors are both finding benefits from the approach. As one investment analyst put it recently: “We might not be particularly interested in every specific issue mentioned in a CSR report. But the presence of good CSR reporting tells us there is good CSR management. And that tells the company as a whole is well-managed.”[15]

Viewed in this light, the quality of the annual report becomes a proxy for the quality of the management team. Narrative reporting is a developing area. All companies are learning. But some companies are clearly taking a lead and developing emerging best practice in different areas[11],[12],[13]. Better reporting not only has the potential to create better relationships between the company and the external constituencies that matter most. It also improves the internal leadership of the business by focusing decision-makers on the real drivers of enduring success. That is the self-interest that is driving some companies to extend their performance in this area.

Other companies should watch the leaders, and apply whatever innovations are most useful to their own situations. The results would then not only be improved dialogue and performance for individual businesses, but also the creation of an environment in which less regulation is needed – because good accountability increases self-regulation and regulation by stakeholder accountability. This is part of the package, along with ‘comply or explain’ and a strong media, which makes for robust governance and reduces the need for imposed regulation.

In 1998 we published our report ‘Sooner, Sharper, Simpler: A lean vision of the inclusive annual report.’ This was intended to challenge companies to re-examine and improve their approach to communication. It identified a number of key principles that still hold true, and continue to be a foundation for the work of Tomorrow’s Company in the field of reporting. It also offers companies a scorecard by which to assess their own reports and benchmark themselves against others.

THOSE PRINCIPLES ARE:

- Improve company decision-making Report on the key drivers of long-term value and thereby focus the minds and priorities of senior management

- Put judgment before compliance Create frameworks which allow companies the flexibility to exercise and then explain their judgment in promoting the success of the company, and lift their sights beyond merely complying with an external standard.

- Improve investor decision-making Enable investors to compare the prospects and performance of companies, and thereby focus the financial system on long-term value creation to the benefit of the entire economy and those who have a diversified exposure to it.

- Make reports more accessible Liberate companies to convey information with the minimum of repetition, and allow them to cross-refer readers to other information, so that they can create a core narrative which captures, in one place, all the key information and context that is needed to form an overall assessment of the company.

- Improve communication and trust without compromising the accountability of companies to shareholders, help employees, the community, regulators and all stakeholders to form a total picture of the company, what it stands for, and where it is going.

References:-::

***************************************************

DR. BHAVESH A. LAKHANI

Faculty, Shri k.K. Shastri Government Commerce College,

Maninagar, Khokhra Road, Ahmedabad-8

&

DR. GURRUDUTTA P. JAPEE

Faculty, S.M.Patel Institute of Commerce,

Law Garden, Ahmedabad-6

Home | Archive | Advisory Committee | Contact us